Teresa and Marvin Bradley can’t say for sure how they got the coronavirus. Maybe Ms. Bradley, a Michigan nurse, brought it from her hospital. Maybe it came from a visiting relative. Maybe it was something else entirely.

What is certain — according to new federal data that provides the most comprehensive look to date on nearly 1.5 million coronavirus patients in America — is that the Bradleys are not outliers.

Racial disparities in who contracts the virus have played out in big cities like Milwaukee and New York, but also in smaller metropolitan areas like Grand Rapids, Mich., where the Bradleys live. Those inequities became painfully apparent when Ms. Bradley, who is Black, was wheeled through the emergency room.

“Everybody in there was African-American,” she said. “Everybody was.”

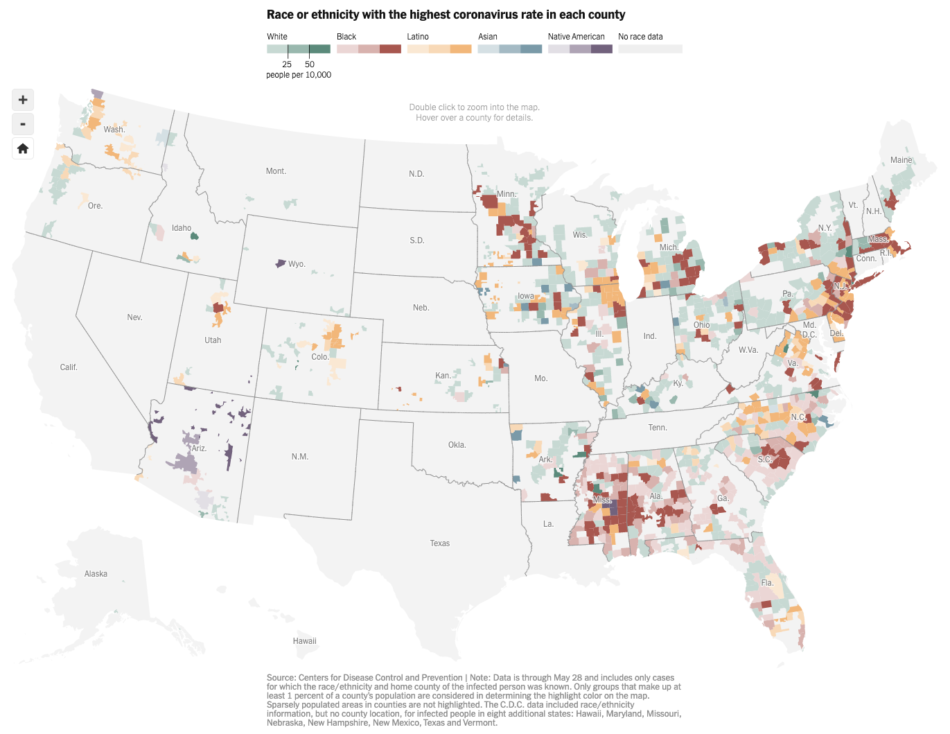

Early numbers had shown that Black and Latino people were being harmed by the virus at higher rates. But the new federal data — made available after The New York Times sued the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — reveals a clearer and more complete picture: Black and Latino people have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus in a widespread manner that spans the country, throughout hundreds of counties in urban, suburban and rural areas, and across all age groups.

Latino and African-American residents of the United States have been three times as likely to become infected as their white neighbors, according to the new data, which provides detailed characteristics of 640,000 infections detected in nearly 1,000 U.S. counties. And Black and Latino people have been nearly twice as likely to die from the virus as white people, the data shows.

The disparities persist across state lines and regions. They exist in rural towns on the Great Plains, in suburban counties, like Fairfax County, Va., and in many of the country’s biggest cities.

“Systemic racism doesn’t just evidence itself in the criminal justice system,” said Quinton Lucas, who is the third Black mayor of Kansas City, Mo., which is in a state where 40 percent of those infected are Black or Latino even though those groups make up just 16 percent of the state’s population. “It’s something that we’re seeing taking lives in not just urban America, but rural America, and all types of parts where, frankly, people deserve an equal opportunity to live — to get health care, to get testing, to get tracing.”

The data also showed several pockets of disparity involving Native American people. In much of Arizona and in several other counties, they were far more likely to become infected than white people. For people who are Asian, the disparities were generally not as large, though they were 1.3 times as likely as their white neighbors to become infected.

The new federal data, which is a major component of the agency’s disease surveillance efforts, is far from complete. Not only is race and ethnicity information missing from more than half the cases, but so are other epidemiologically important clues — such as how the person might have become infected.

And because it includes only cases through the end of May, it doesn’t reflect the recent surge in infections that has gripped parts of the nation.

Still, the data is more comprehensive than anything the agency has released to date, and The Times was able to analyze the racial disparity in infection rates across 974 counties representing more than half the U.S. population, a far more extensive survey than was previously possible.

Disparities in the suburbs

For the Bradleys, both in their early 60s, the symptoms didn’t seem like much at first. A tickle at the back of the throat.

But soon came fevers and trouble breathing, and when the pair went to the hospital, they were separated. Ms. Bradley was admitted while Mr. Bradley was sent home. He said he felt too sick to leave, but that he had no choice. When he got home, he felt alone and uncertain about how to treat the illness.

It took weeks, but eventually they both recovered. When Mr. Bradley returned to work in the engineering department of a factory several weeks later, a white co-worker told Mr. Bradley that he was the only person he knew who contracted the virus.

By contrast, Mr. Bradley said he knew quite a few people who had gotten sick. A few of them have died.

“We’re most vulnerable to this thing,” Mr. Bradley said.

In Kent County, which includes Grand Rapids and its suburbs, Black and Latino residents account for 63 percent of infections, though they make up just 20 percent of the county’s population. Public health officials and elected leaders in Michigan said there was no clear reason Black and Latino people in Kent County were even more adversely affected than in other parts of the country.

Among the 249 counties with at least 5,000 Black residents for which The Times obtained detailed data, the infection rate for African-American residents is higher than the rate for white residents in all but 14 of those counties. Similarly, for the 206 counties with at least 5,000 Latino residents analyzed by The Times, 178 have higher infection rates for Latino residents than for white residents.

“As an African-American woman, it’s just such an emotional toll,” said Teresa Branson, the deputy administrative health officer in Kent County, whose agency has coordinated with Black pastors and ramped up testing in hard-hit neighborhoods.

Experts point to circumstances that have made Black and Latino people more likely than white people to be exposed to the virus: Many of them have front-line jobs that keep them from working at home; rely on public transportation; or live in cramped apartments or multigenerational homes.

“You literally can’t isolate with one bathroom,” said Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist II, who leads Michigan’s task force on coronavirus racial disparities.

‘We just have to keep working’

Latino people have also been infected at a jarringly disparate rate compared with white people. One of the most alarming hot spots is also one of the wealthiest: Fairfax County, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Three times as many white people live there as Latinos. Yet through the end of May, four times as many Latino residents had tested positive for the virus, according to the C.D.C. data.

With the median household income in Fairfax twice the national average of about $60,000, housing is expensive, leaving those with modest incomes piling into apartments, where social distancing is an impossibility. In 2017, it took an annual income of almost $64,000 to afford a typical one-bedroom apartment, according to county data. And many have had to keep commuting to jobs.

Diana, who is 26 and did not want her last name used out of fear for her husband’s job, said her husband got sick at a construction site in April. She and her brother, who also works construction, soon fell ill, too. With three children between them, the six family members live in a two-bedroom apartment.

Diana, who was born in the United States but moved to Guatemala with her parents as a small child before returning to this country five years ago, is still battling symptoms. “We have to go out to work,” she said. “We have to pay our rent. We have to pay our utilities. We just have to keep working.”

At Culmore Clinic, an interfaith free clinic serving low-income adults in Fairfax, about half of the 79 Latino patients who tested for the virus have been positive.

“This is a very wealthy county, but their needs are invisible,” said Terry O’Hara Lavoie, a co-founder of the clinic. The risk of getting sick from tight living quarters, she added, is compounded by the pressure to keep working or quickly return to work, even in risky settings.

The risks are borne out by demographic data. Across the country, 43 percent of Black and Latino workers are employed in service or production jobs that for the most part cannot be done remotely, census data from 2018 shows. Only about one in four white workers held such jobs.

Also, Latino people are twice as likely to reside in a crowded dwelling — less than 500 square feet per person — as white people, according to the American Housing Survey.

The national figures for infections and deaths from the virus understate the disparity to a certain extent, since the virus is far more prevalent among older Americans, who are disproportionately white compared with younger Americans. When comparing infections and deaths just within groups who are around the same ages, the disparities are even more extreme.

Latino people between the ages of 40 and 59 have been infected at five times the rate of white people in the same age group, the new C.D.C. data shows. The differences are even more stark when it comes to deaths: Of Latino people who died, more than a quarter were younger than 60. Among white people who died, only 6 percent were that young.

Jarvis Chen, a researcher and lecturer at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, said that the wide racial and ethnic disparities found in suburban and exurban areas as revealed in the new C.D.C data should not come as a surprise. The discrepancies in how people of different races, ethnicities and socioeconomic statuses live and work may be even more pronounced outside of urban centers than they are in big cities, Dr. Chen said.

“As the epidemic moves into suburban areas, there are good reasons to think that the disparities will grow larger,” he said.

The shortfalls of the government’s data

The Times obtained the C.D.C. data after filing a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit to force the agency to release the information.

To date, the agency has released nearly 1.5 million case records. The Times asked for information about the race, ethnicity and county of residence of every person who tested positive, but that data was missing for hundreds of thousands of cases.

C.D.C. officials said the gaps in their data are because of the nature of the national surveillance system, which depends on local agencies. They said that the C.D.C. has asked state and local health agencies to collect detailed information about every person who tests positive, but that it cannot force local officials to do so. Many state and local authorities have been overwhelmed by the volume of cases and lack the resources to investigate the characteristics of every individual who falls ill, C.D.C. officials said.

Even with the missing information, agency scientists said, they can still find important patterns in the data, especially when combining the records about individual cases with aggregated data from local agencies.

Still, some say the initial lack of transparency and the gaps in information highlight a key weakness in the U.S. disease surveillance system.

“You need all this information so that public health officials can make adequate decisions,” said Andre M. Perry, a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at The Brookings Institution. “If they’re not getting this information, then municipalities and neighborhoods and families are essentially operating in the dark.”

Higher cases, higher deaths

The higher rate in deaths from the virus among Black and Latino people has been explained, in part, by a higher prevalence of underlying health problems, including diabetes and obesity. But the new C.D.C. data reveals a significant imbalance in the number of virus cases, not just deaths — a fact that scientists say underscores inequities unrelated to other health issues.

The focus on comorbidities “makes me angry, because this really is about who still has to leave their home to work, who has to leave a crowded apartment, get on crowded transport, and go to a crowded workplace, and we just haven’t acknowledged that those of us who have the privilege of continuing to work from our homes aren’t facing those risks,” said Dr. Mary Bassett, the Director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University.

Dr. Bassett, a former New York City health commissioner, said there is no question that underlying health problems — often caused by factors that people cannot control, such as lack of access to healthy food options and health care — play a major role in Covid-19 deaths.

But she also said a big determinant of who dies is who gets sick in the first place, and that infections have been far more prevalent among people who can’t work from home. “Many of us also have problems with obesity and diabetes, but we’re not getting exposed, so we’re not getting sick,” she said.

The differences in infection case rates are striking, said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“Some people have kind of waved away the disparities by saying, ‘Oh, that’s just underlying health conditions,’” Dr. Nuzzo said. “That’s much harder to do with the case data.”

In June, C.D.C. officials estimated that the true tally of virus cases was 10 times the number of reported cases. They said they could not determine whether these unreported cases had racial and ethnic disparities similar to those seen in the reported infections.

But they said that more-severe infections — which are more often associated with underlying health conditions, and with people seeking medical care — are more likely to be recorded as cases.

That difference in the reporting of cases might explain some portion of the race and ethnicity disparities in the number of documented infections, C.D.C. officials said. But they said that it was also clear that there have been significant disparities in the number of both deaths and cases.

Methodology

To measure how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting various demographic groups in the United States, The New York Times obtained a database of individual confirmed cases along with characteristics of each infected person from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The data was acquired after The Times filed a Freedom of Information Act suit. The C.D.C. provided data on 1.45 million cases reported to the agency by states through the end of May. Many of the records were missing critical information The Times requested, like the race and home county of an infected person, so the analysis was based on the nearly 640,000 cases for which the race, ethnicity and home county of a patient was known.

The data allowed The Times to measure racial disparities across 974 counties, which account for about 55 percent of the nation’s population, a far wider look than had been possible previously. Infection and death rates were calculated by grouping cases in the C.D.C. data by race, ethnicity and age group, and comparing the totals with the most recent Census Bureau population estimates for each county.

For national totals, The Times calculated rates based on both the actual population and the age-adjusted population of each county. The age adjustment accounts for the higher prevalence of the virus among older U.S. residents and the varying age patterns of different racial and ethnic groups. The national totals exclude data for eight states for which county-level information was not provided, but each of those states also showed a racial disparity in case rates.