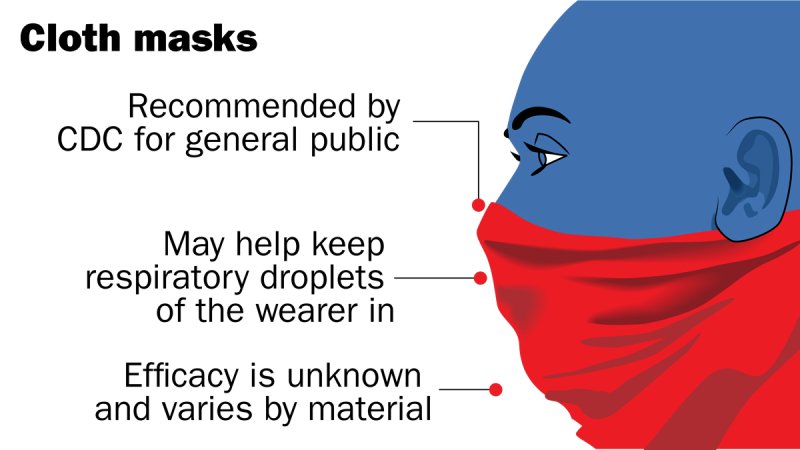

When the new coronavirus first hit the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) told people not to wear face masks unless they were sick or caring for someone who was. Masks help capture some of a sick person’s respiratory droplets, which might otherwise spread the virus. In early April, however, the CDC began advising all people to wear non-medical “masks”—any fabric that covers the nose and mouth—when they leave home. The reason for the shift? Scientists now know that many people who are infected with the coronavirus show no symptoms yet can still spread it to others. There’s no way to tell who’s sick and who’s not.

But the efficacy of homemade masks is not scientifically settled. Studies do find that masks can help prevent a sick person from spreading some viruses to others—and may even marginally protect healthy people from becoming ill. “Across these studies, it’s quite consistent that there’s some small effect and there’s no risk associated with wearing masks,” says Allison Aiello, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health.

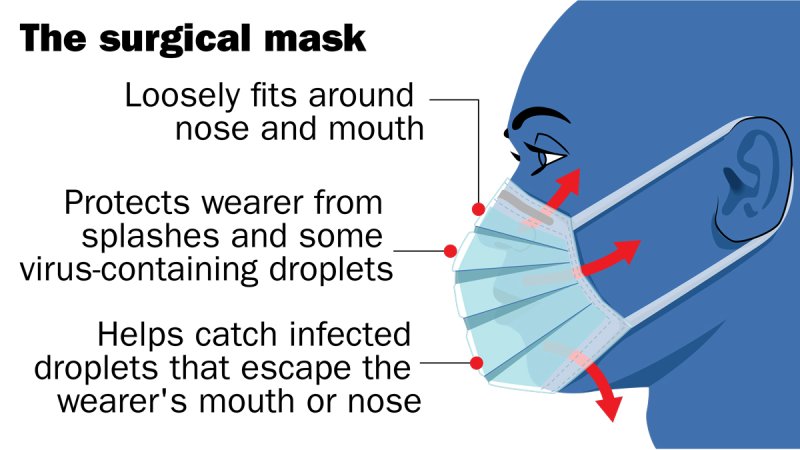

But this research is on surgical masks: loose-fitting masks designed to protect the wearer from outside virus-containing splashes and droplets, and to catch infected droplets that escape the wearer’s mouth or nose.

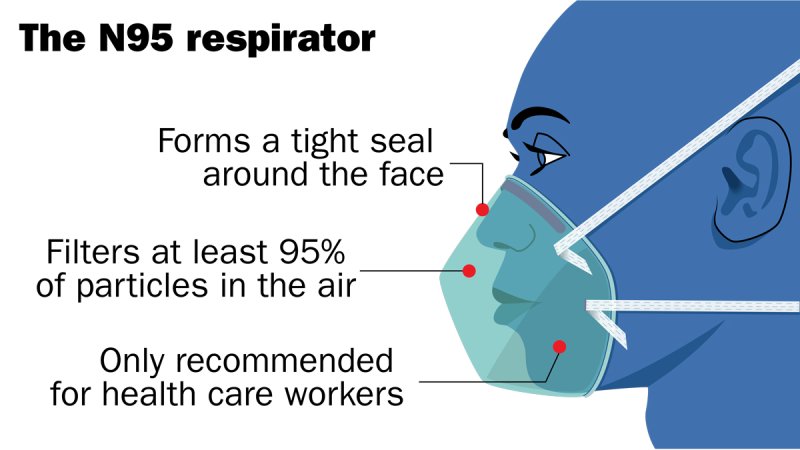

Neither these nor N95 respirators—tight-fitting facial devices that filter out small particles from the air—are recommended for the general public due to a shortage for health care workers.

It’s unclear if the research on masks would also apply to homemade face coverings, but Aiello and others believe that physical facial barriers are worth wearing during the pandemic even in the absence of strong evidence. As the authors of an analysis published April 9 in the BMJ put it, “In the face of a pandemic the search for perfect evidence may be the enemy of good policy. As with parachutes for jumping out of aeroplanes, it is time to act without waiting for randomised controlled trial evidence.”

Few studies have tested homemade masks. One published in 2013 found that T-shirt masks were about a third as effective as surgical masks at filtering small infectious particles. That’s “better than nothing,” says study author Anna Davies, a research coordinator at the University of Cambridge, but “there’s so much inherent variability in a homemade mask.” Other research found that homemade masks may actually increase the risk of infection if they’re not washed often enough, since damp fabric can breed pathogens.

The bottom line is that wearing a mask is probably a sensible move—as long as you clean it often, wash your hands, refrain from touching your face and continue to keep a safe distance from other people. But there’s not robust evidence that the DIY kind will definitely stop you or others from getting sick.